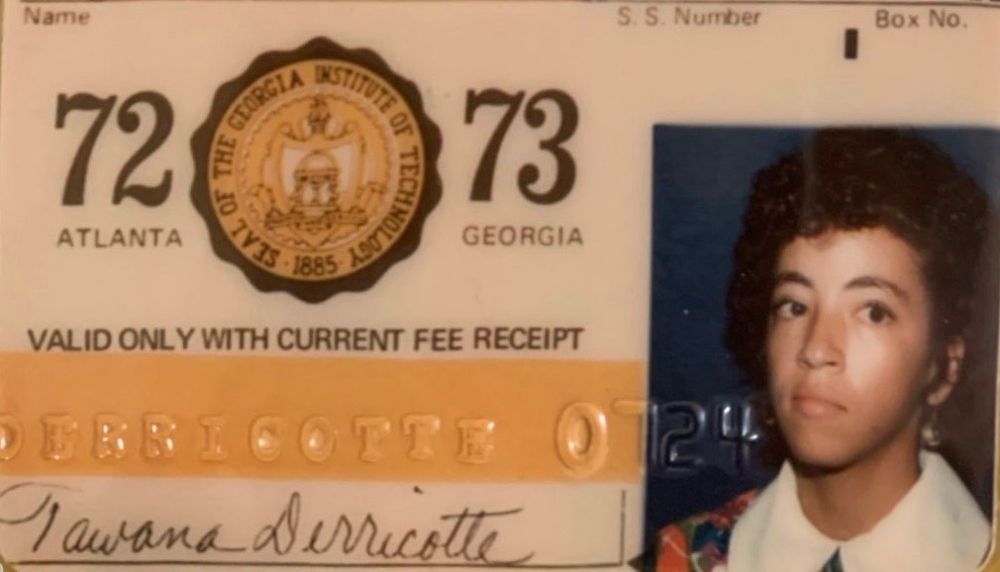

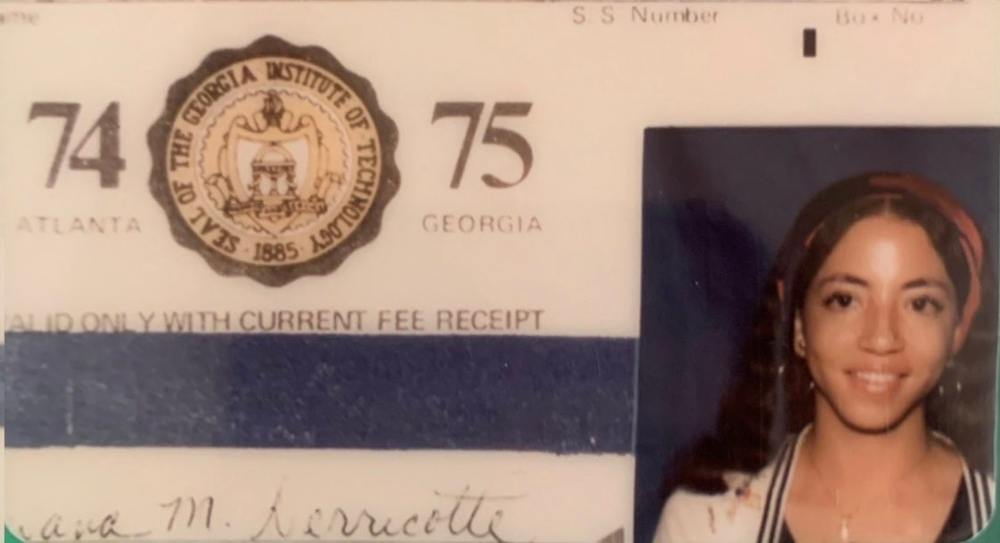

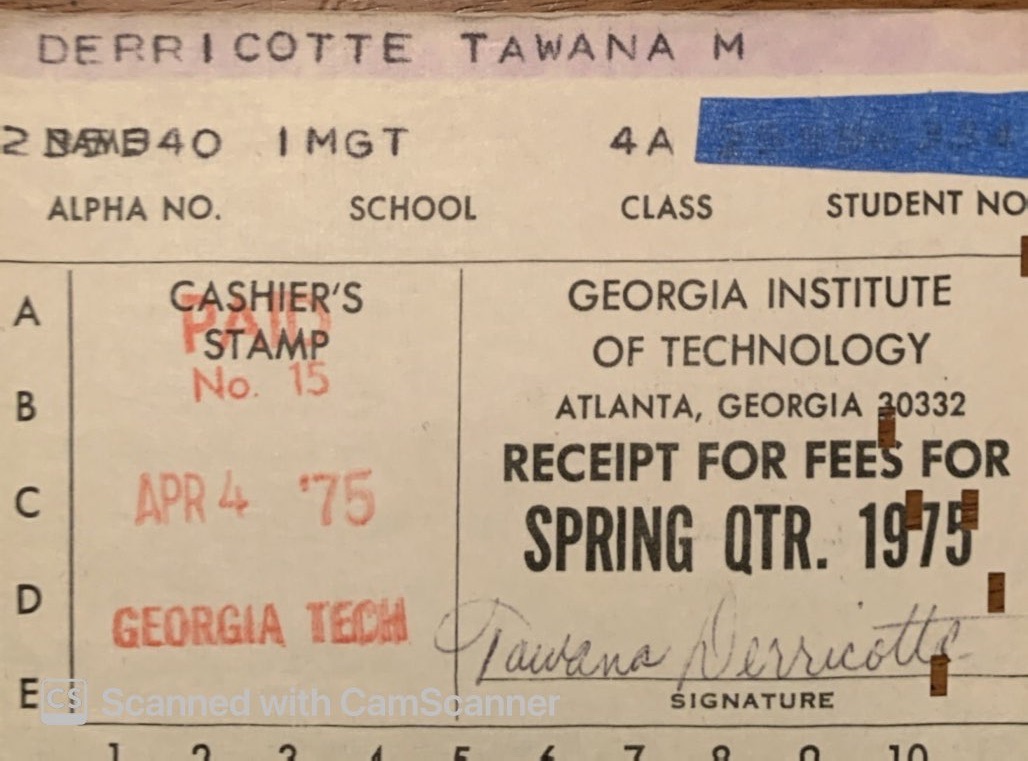

When Tawana Miller stepped foot onto Georgia Tech’s campus in the heated late summer of 1972, the university was just a little over 10 years removed from the first semester it opened its doors to all students as a desegrated campus.

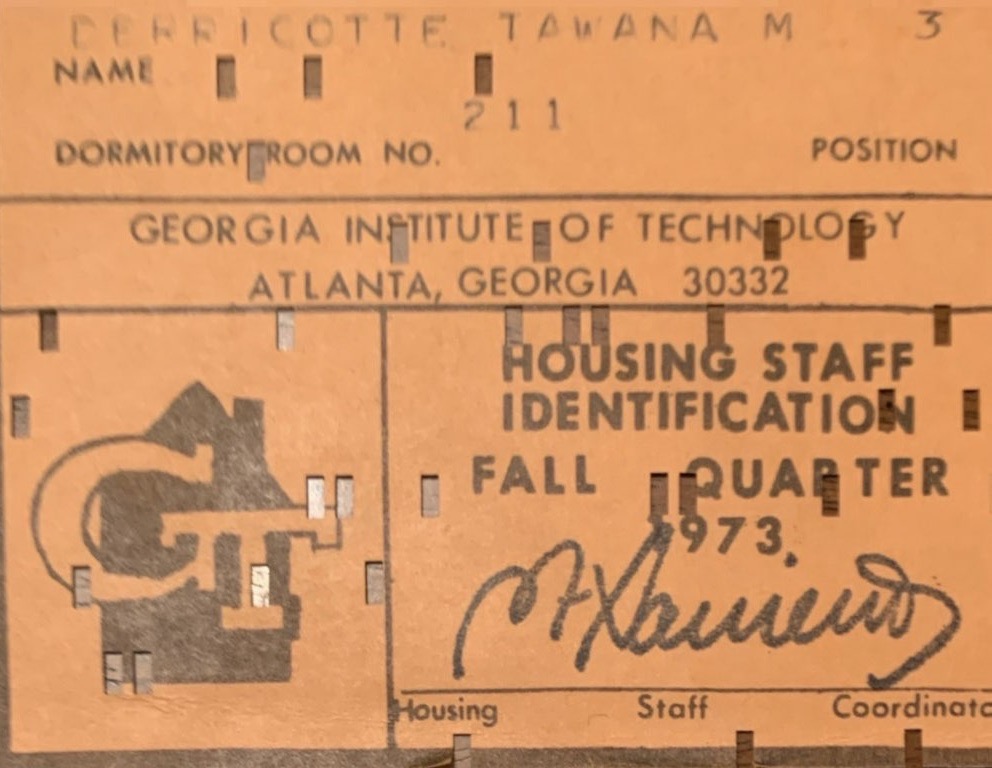

Eleven years was long enough that Miller’s presence coming and going from Fitten dorm, taking notes in Dr. Phil Adler’s class, or dancing in a flag corps routine was no longer surprising. But to some, it remained unwelcome.

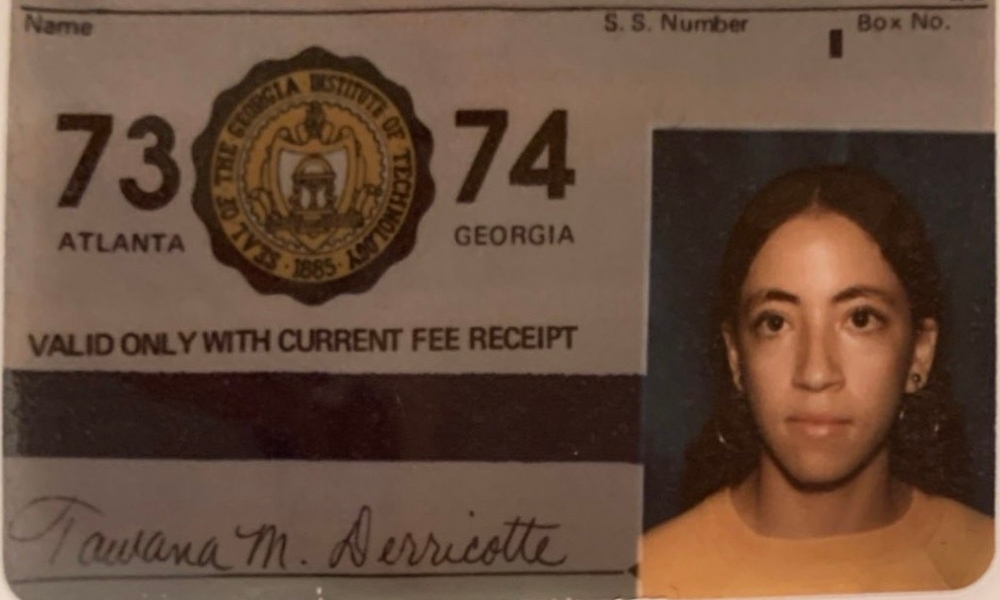

Despite the difficulties inherent in navigating a Georgia Tech education while Black in a post-segregation era, Miller made it to the other side of those four years. She started at Tech alongside five other Black women. Slowly, some transferred to Spelman and some started families. When Miller graduated in 1976 with a Bachelor of Science in Industrial Management, she was the last one standing.

A Foundation Built on Education

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say Miller’s educational foundation was built on the sturdy spines of World Book Encyclopedias. Her parents were co-division managers at World Book, establishing relationships and, of course, selling the thick tomes across the region and throughout the Atlanta public school system. From an early age, Miller learned to see education as instrumental to change and educators as prime facilitators in that change.

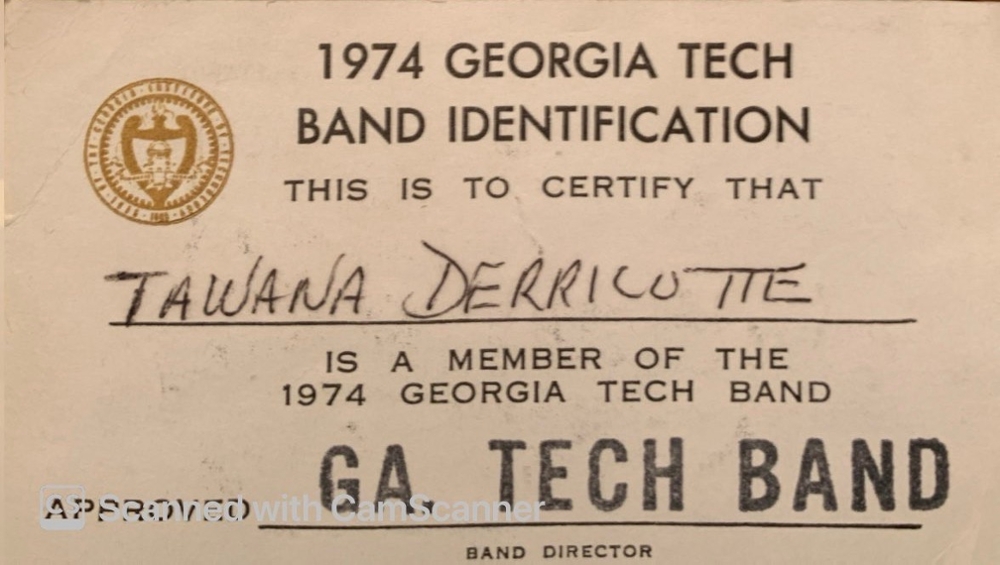

Miller attended area parochial and public schools until her graduation from Therrell High School; she admittedly had no idea what she wanted to be. She did know, however, what she was good at. Music, for starters. She played the French horn, violin, guitar, and piano. Her academic strengths lay in math and science. During her senior year, testing results placed her second highest in the state of Georgia for math.

Despite her academic success, her options for college were limited. Spelman was too expensive. Her mother had attended, but never graduated due to the steep costs. Miller sent her applications off to Georgia State University, Emory, Georgia Tech, and, here’s-to-hoping, MIT. She told herself that wherever she was admitted would determine her course of study. If Emory: music. If GSU: actuarial science. If Georgia Tech: accounting.

Her future remained wide-open after the acceptance letters came rolling in from everywhere except MIT. Emory offered Miller a scholarship, but it wouldn’t be enough to support her through all four years. Still vacillating, Miller’s decision became set in stone when Georgia Tech’s acceptance letter was followed a few months later by a scholarship. The Bobby Dodd athletic scholarship would fully cover her tuition. Laughing at the scholarship’s “athletic” qualifier, but grateful all the same, Miller accepted.

Getting In and Getting Out

Miller knew that she wanted to graduate from Georgia Tech in no less than four years. But after the divisive “look to your left and look to right, one of you will not be here at graduation” speech was followed by the consistent barbed meanness of racial inequities still drawing breath across campus, she became even more determined to make it out quickly with her dignity and her degree.

“I was hell bent and determined to get in and get out with my degree as fast as possible,” Miller explained. “No matter how you get beat up or belittled, you just have to keep going, stubborn and determined to hold on and get the degree.”

Miller wasn’t without friends, even as her Black female classmates dwindled away. Female students, Black or white, were still a rarity on campus, and after Miller declared her Industrial Management major, her core classes were made up by an increasingly larger group of Black male student athletes who seemed to consistently do well on tests. She wondered at how their success came with greater ease than hers did.

“I attended several classes with a group of Black football players,” Miller recalled. “I noticed that they seemed to be performing well on all the tests. I wondered how they could spend most of their time practicing on the field and then test well. I was not playing a sport, studying all of the time, and still not getting straight A’s. Some of the guys noticed my frustration and took the time to share their strategies and techniques for success. All the athletes had tutors to help them in classes. They had study guides and other resources, whereas I was doing all the research on my own.”

While Cornell Seymour, Dwain Carroll, and Karl “PeeWee” Barnes excelled on the football field, more importantly for Miller, they became her biggest supporters, teaching her to work smarter, not harder.

Miller’s time at Tech was marked by the struggle to build a support system and find success in the classroom. She maintained her scholarship funding throughout her four years, holding especially tight to it through one mind-numbingly difficult math class. Even that experience, Miller conceded, taught her something valuable and made her more resilient.

There were also moments in the classroom and with friends that punctuated her time at Tech with glimmers of growth and joy.

There were the minutes on the football field with the flag corps, of which she was one of the founding members and the first Black woman member. In the classroom, Miller described being in the presence of iconic professor of Management Dr. Phil Adler as “life changing.” He helped her see that Georgia Tech was not a beast intent on swallowing her whole, but rather, a partner in her future success.

A Legacy of Resilience

When Miller accepted her diploma in 1976, she suspected she was one of the first Black women to graduate from Georgia Tech with an undergraduate degree, but it seemed unimportant to the university, history, and everyone else.

“I had my degree, and there were so many other things happening in the world that made my accomplishment seem minor and only meaningful to me,” Miller said. “It honestly wasn’t really a big deal to me. My response was to put this on the back burner, move on, and live my life.”

Miller’s accomplishment sat unrecognized and gathering dust. It sat through the birth of her four children, her time as a teacher, her master’s in middle childhood education, and her doctorate in education. Miller describes how her accomplishment was brought to light with curiosity and intent.

It began when her daughter, Adria Miller Gaines, was working at Georgia Tech’s Office of Minority Educational Development (OMED) and mentioned that she thought her mother was among the first Black female undergraduates to matriculate at Georgia Tech.

“Another student started doing a bit of research,” Miller recalled. “And this was followed by other Black Georgia Tech alumni Cornell Seymour (now deceased), Dwain Carroll, and Karl Barnes mentioning my name to Marilyn Somers at Living History for an interview. Then the wheels started turning and BINGO. It was revealed that I actually was correct.”

During Black History Month in 2017, Cornell Seymour presented her with a plaque to acknowledge her accomplishment. Since then, Miller has also received the 2022 Ronald L. Yancey Trailblazer Award from the Georgia Tech Black Alumni Organization, and she looks forward to the tribute that will be included in the forthcoming installation celebrating the accomplishments of Georgia Tech’s women faculty, staff, and alumna.

While her Georgia Tech experience wasn’t without the adversities common to a 1970s desegregated South, Tawana Miller graduated empowered by her experience and prepared to pursue a successful career in education. For this, Tawana Miller proudly bleeds gold.